- Home »

- Business Bankruptcy »

- Dealing with Corporate Distress 05: The Lifecycle of a Chapter 11 Case

Dealing with Corporate Distress 05: The Lifecycle of a Chapter 11 Case

The ABCs of ABCs, Business Bankruptcy & Corporate Restructuring/Insolvency

[Authors’ Note: Before going any further, read Installment 4: Chapter 11—If You’ve Seen One, You’ve Seen Them All. While you can generally read any installment in this series in any order or even by itself, this one is an exception…]And now, we present to you, the five stages of a “typical” chapter 11 case (subject to the caveats you read in our previous installment). By the way, make sure you read to the end so you can see what a traditional chapter 11 is, and is not.

The Five Stages of a “Typical” Chapter 11

Stage 1: Prepetition Planning

By our measure, the first stage of the chapter 11 timeline begins before (preferably long before) a chapter 11 is filed—prepetition (the date a bankruptcy is filed is its “petition date“).

Planning, as is oft-stated, is key to success in any endeavor. Yet the single most common mistake we see distressed companies make is waiting too long to plan. It doesn’t matter how large and sophisticated the company or its owner(s) are, a variety of factors too often conspire to cause a company to wait longer than it should.

There are a number of actions a debtor (i.e., the distressed company) can take to turn itself around, to restructure its debt, or to otherwise resolve its financial distress without having to resort to bankruptcy. These options are not like fine wine—they don’t get better with age. Rather, as time passes, optionality decreases.

You should think of the first stage beginning when the debtor engages counsel to assist in filing chapter 11, if necessary. It is at that point the debtor can begin to properly analyze its situation with reference to the legal tools available to it. Analysis is followed (or, better yet, accompanied) by action. Such action commonly includes (or should include):

- Making operational changes to the business, with a priority on generating and conserving cash;

- Engaging key constituents (starting with senior secured lenders, critical vendors, and any party who has or is close to getting a judgment in a lawsuit against the company) in a new dialogue; or

- Shoring up financial controls and reporting functions.

During this first stage, chapter 11 should not be considered a foregone conclusion unless there are clear reasons for doing so. There may be cheaper, more effective means of achieving the debtor’s goals. Alternatives to chapter 11 are discussed in Installment 7, and you can also review more articles on bankruptcy alternatives.

Preparing a company for chapter 11 can be expensive (both in terms of legal and other professional fees, and in terms of the distraction it can cause among the company’s executives), but it is sometimes smart (if not necessary) to begin chapter 11 preparation before making the decision to file. The following considerations may drive chapter 11 “contingency planning” sooner rather than later:

- The size and complexity of the company

- The need to make a credible threat that the company is willing and able to file chapter 11, if necessary

- The preferences of the company’s various constituents

- Seasonality issues

- Threats of foreclosure, passing court deadlines, and the like

- Statutes of limitations and appeal deadlines

- Judgment calls about the likelihood that a chapter 11 filing is inevitable

A distressed business and its restructuring/insolvency attorney must engage in a balancing act. Early and deeper preparation for a potential chapter 11 is costly but can significantly decrease the likelihood that chapter 11 will be necessary. At the same time, early prep significantly increases the likelihood that if a chapter 11 is necessary, it will be successful.

Even if unprepared, it takes surprisingly little effort or action to file a chapter 11 case, because it requires very little paperwork and can be done online through the bankruptcy court’s electronic filing system. Filing chapter 11 immediately imposes an automatic stay against all creditor collection efforts. That is, all creditors are immediately prevented from trying to get the debtor to pay for any debts incurred before the petition date. That’s the good news.

First Day Motions

The problem with filing a bankruptcy petition and its required attachments with nothing more (i.e., a “naked petition”) is twofold. First, there are other documents that must accompany the chapter 11 petition or follow shortly thereafter. That’s more paper. The second issue is that the automatic stay also prohibits a debtor from paying any debts that arose or came due before the petition date, even if it wants to. That’s a bigger problem.

Take for example, XYZ Co.:

XYZ Co. normally pays its employees’ wages two weeks in arrears, every other Thursday. XYZ files chapter 11 on a Tuesday, two days prior to a payday. At that moment in time, XYZ owes its employees for 12 days of work and by Thursday it will owe its them for a full two weeks—all of which was prepetition. Because of the automatic stay, XYZ cannot pay its employees for those two weeks without court authority.

The way this is dealt with is by filing a motion asking the court to permit the payment. Sounds like it should be an easy order for a court to grant, right? Well, it almost always is. Sounds like most other creditors wouldn’t object, right? They seldom do.

The “Wages Motion” (as it is often referred to as a shorthand) is usually a pretty non-controversial first day motion. It is, nonetheless, commonly necessary to prepare one. And that requires due diligence by the company’s attorneys; time away from management to respond to those due diligence requests; and time to negotiate, draft, review, revise, and finalize the motion. All of this costs time and money. And the Wages Motion is just one of a number of first day motions that often must be filed.

And that’s just on the legal side. A chapter 11 case of a company of any substantial size often requires (or at least benefits tremendously from) help from outside financial, operational, and other consultants.

For another example of a need for a first day motion: suppose XYZ Co. has a secured line of credit with a bank. Most security agreements grant the lender a security interest in a debtor’s cash, and Bankruptcy Code § 363(c)(2) specifically prohibits a debtor from using such cash unless the secured creditor (1) consents to its use; or (2) the debtor gets court approval to use the cash without the creditor’s consent. This assumes the debtor’s cash flow is sufficient to support its operation in chapter 11 plus the additional costs associated with running the chapter 11 case. If that’s not the situation, then a motion for DIP financing becomes necessary. (Not up-to-date on your financing options? Read more short, plain English articles about cash collateral and DIP financing.)

Pulling the Camera Back

There are numerous examples of other business disruptions a debtor must prepare for before filing a chapter 11 case. Again, that is what first day motion practice is for: a debtor can prepare for and address many of these issues by filing first day motions with the bankruptcy court—usually on an emergency basis—to seek relief from the restrictions imposed by the Bankruptcy Code. Such “first day relief” helps a debtor continue operating its business with as little interruption as possible so that it can try to achieve its goals in chapter 11. We discuss the concept and mechanics of first day motions in greater depth in Installment 6 of this series.

Communication—The Key to Any Relationship

The most important work—and the most value added by—experienced restructuring counsel happens outside the four walls of any courtroom. One example of such work concerns communications.

As the expression goes, perception is reality. A company needs a plan to communicate with its various constituents. For example, vendors need to know how they will be paid for their postpetition sales to the debtor; and customers need to know whether they can rely on their supplier (i.e., the debtor) to continue supplying their needs. If you don’t want employees to walk off the job out of fear they may be fired without notice, that also needs to be addressed. Good communications can also help in the courtroom, and the first day motions are a debtor’s first opportunity to tell its story—explain to a court why it is in chapter 11, what its goals are for the case, and how it will achieve its goals.

Stage 2: Early Postpetition / “First Days” of a Chapter 11 Case

We define Stage 2 as the period triggered immediately upon the petition date. As we explain above, along with filing a petition for chapter 11 relief (the formal means by which a chapter 11 case is filed), a debtor who has planned ahead will file its first day motions and request that the bankruptcy court schedule a hearing on them as soon as possible. The resulting “first day hearing” usually happens a day or two after the petition date.

At the first day hearing, counsel for the debtor will present the first day motions to the bankruptcy court, addressing any concerns the bankruptcy judge may have with the relief being sought under each first day motion, as well as addressing any objections creditors may have. At the conclusion of the first day hearing, the bankruptcy court will enter a series of orders granting some or all of the first day motions—often on an interim basis.

The reason courts grant first day relief on an interim basis is because the bankruptcy judge has to balance the competing interests of the debtor and its creditors. The debtor needs immediate relief to operate its business postpetition, but creditors are entitled to adequate notice and opportunity to object to the first day motions to avoid being prejudiced early in the case. Thus, the court will enter interim orders granting first day motions, and will set a later date for all parties to return and be heard before final orders are entered.

Implementing a Communications Plan

All manner of communications may flood into the debtor immediately after a chapter 11 filing. Employees, with no understanding of chapter 11, are also likely to have questions. This is why, in addition to the activities taking place in court during the first days of a chapter 11 case, the debtor’s internal and external communications plans need to be implemented on the petition date.

Committee Formation

During the first days of a chapter 11 case, the U.S. Trustee will solicit interest from the debtor’s largest unsecured creditors to serve on an official committee of unsecured creditors (unless the case is: proceeding under subchapter V; a small business chapter 11 case; or a single asset real estate case, where committees are not statutorily required). The committee is charged with representing the interests of all of the debtor’s unsecured creditors.

If there is enough interest from creditors, the U.S. Trustee will hold a “formation meeting” where creditors interested in serving on the committee can attend (in person or telephonically, depending on where the case is filed) and be appointed to the committee. Representatives of the debtor (usually its bankruptcy counsel and one or more of the debtor’s business people) typically appear at the formation meeting and give a short presentation to the parties in attendance This happens before the U.S. Trustee forms the committee and appoints creditors to serve. Committees differ in size but are usually comprised of 3-9 creditors depending on the size of the case, interest expressed, and diversity of interests among the creditor body.

Working with the Subchapter V Trustee

If the chapter 11 is a subchapter V case, a subchapter V trustee (“Sub V trustee”) will be assigned to the case. The Sub V trustee’s role is to supervise and monitor the case, and participate with the debtor in plan development and confirmation.

The Sub V trustee does not normally assume control of the debtor’s bankruptcy estate, as a “traditional” chapter 11 trustee does. The trustee has additional duties under subchapter V, including accounting for property the debtor receives during its case, examining proofs of claim, and objecting to them if necessary, and potentially serving as disbursing agent for creditors under the debtor’s plan, among others.

While consensual plans are not required in a subchapter V case, the process is structured toward this goal, so debtors are encouraged to work with their Sub V trustees to develop and confirm a plan that all parties consent to. On the other hand, the ability to cram down on unsecured creditors is certainly far greater in subchapter V than out.

Disclosure & Transparency: Immediate Postpetition Meetings

Chapter 11 also imposes numerous obligations on a debtor with respect to information sharing.

Soon after the petition date, every chapter 11 debtor must prepare and file schedules of its assets and liabilities, as well as additional disclosures related to the debtor’s financial affairs. Shortly after filing its chapter 11 petition, the debtor must attend two more meetings conducted by the U.S. Trustee’s office.

The first meeting, known as an “initial debtor interview” or “IDI,” is a meeting between a bankruptcy analyst—an accounting professional employed by the U.S. Trustee’s office—and a representative of the debtor versed in the debtor’s financial affairs. Counsel for the debtor will also attend this meeting.

During the IDI, the bankruptcy analyst will ask questions relating to the debtor’s financials, and may ask specific questions about items disclosed in the debtor’s bankruptcy schedules and statement of financial affairs (if filed by this time) to better understand the nature of these items and whether any additional information needs to be disclosed by the debtor in relation to these matters.

Following the IDI, § 341 of the Bankruptcy Code requires that the U.S. Trustee convene a “meeting of creditors” (also referred to as a “341 meeting”) at which the debtor must appear through one or more representatives with knowledge of the debtor’s financial affairs, to give testimony, under oath and on the record, regarding the debtor’s general financial affairs, bankruptcy schedules and statement of financial affairs, and administration of the chapter 11 case.

While the U.S. Trustee is charged with convening this meeting, all creditors are given notice of the 341 meeting and are allowed to attend and are given the opportunity to question the debtor under oath. The scope of the 341 meeting is limited, and creditors are not permitted to ask the debtor questions that relate only to their specific claims. Instead, the 341 meeting is intended to provide creditors with an understanding of the debtor’s overall financial affairs and administration of its chapter 11 case.

Stage 3: The “Middle” of a Chapter 11 Case

Following the initial flurry of activity in Stages 1 and 2 of the chapter 11 timeline, a debtor’s business operations will typically begin to normalize, and operations will feel more like “business as usual” (at last relatively speaking). The Bankruptcy Code and Bankruptcy Rules do, however, impose many ongoing obligations, powers, and protections on a chapter 11 debtor.

The reasons, generally, are to:

- Enable the debtor a respite from collection activity;

- Foster the rehabilitation of its operations and/or the restructuring of its balance sheet;

- Provide an appropriate level of oversight of the debtor; and, above all

- Maximize the pro rata recovery of creditors in the order of absolute priority.

The Bankruptcy Code and Rules, however, are not sacrosanct.

The debtor, its creditors, and other parties in interest may file motions seeking to override the statutory defaults. Parties may also object to motions that, if granted, would impact the objector’s position. All this activity may occur at any stage in the chapter 11 timeline, though much of it happens in what we denominate as Stage 3. Examples of such activity include the following:

- Continuing disclosure obligations. Transparency is a linchpin in bankruptcy, and the name of the game is disclosure. A chapter 11 debtor must file monthly informational reports about its operations, showing all receipts and disbursements flowing in and out of the business for the prior month. These reports, commonly referred to as the “monthly operating reports” or “MORs,” impose a heightened level of disclosure and transparency a business debtor will likely not be accustomed to. More generally, a chapter 11 debtor and other parties in interest are required to file motions to seek approval before taking certain actions or in order to obtain court approval with respect to other matters. Notice of such motions need to be served on, at least, parties who have filed a proper request for such notices.

- Automatic stay. All action by all creditors to collect on prepetition debts is halted in its tracks by the automatic stay. But any creditor can ask the court to modify the automatic stay.

- Acting outside the ordinary course. If the debtor wants to act outside the ordinary course of business (e.g., sell major assets, take actions that would normally require board approval, etc.), it will need to seek court approval to do so.

- Collecting assets of the estate. Chapter 11 debtors must collect property of their estate for the benefit of creditors. In the event of a liquidating chapter 11, this may mean filing a motion to require a third party to turn over property to the debtor, or filing lawsuits to collect preferences or fraudulent transfers.

- Executory contracts and unexpired leases. Chapter 11 affords debtors the unique ability to take time to assume (and potentially assign to a third party) or reject executory contracts and unexpired leases, in addition to granting them the authority to do so. Some of these motions may be filed as first day motions, but need not be.

- Asset sales. Often times a chapter 11 case will be filed for the purpose of making the debtor’s assets more attractive to buyers, because they can be sold free and clear of claims and interests under § 363 of the Bankruptcy Code. Often an asset sale will constitute the effective “middle” of a bankruptcy case because, once a sale is consummated, the debtor can formulate its exit from bankruptcy under a plan of liquidation or structured dismissal. In any event, whenever a debtor intends to sell assets outside of the ordinary course of its business, it must seek court approval to do so.

- Claim reconciliation. An additional administrative task that may be undertaken in the middle of a chapter 11 case is claims reconciliation. This is a process whereby the debtor compares its records to proofs of claims filed by creditors, and then seeks to reconcile them against one another by agreement or litigation with each creditor.

- Subchapter V cases. Small business debtors electing to proceed under new subchapter V of chapter 11 face some additional requirements in the “middle” of the case. Sixty days into a case, a debtor must appear in court for a status conference with the judge and its Sub V trustee, to report to the court on its efforts to confirm a consensual plan. A debtor must also file a report detailing its efforts 14 days before the status conference.

Stage 4: Plan Formulation & Confirmation, or Structured Dismissal

The real business goals of chapter 11, as stated above, are to:

- Enable the debtor a respite from collection activity

- Foster the rehabilitation of its operations and/or the restructuring of its balance sheet

- Provide an appropriate level of oversight of the debtor

- Above all, maximize the pro rata recovery of creditors in the order of absolute priority1

Whether creditors will be paid primarily from the proceeds of the sale of the debtor’s assets (together, perhaps, with the proceeds of litigation recoveries) or as a result of a classic reorganization (i.e. over time from the ongoing operations of the reorganized debtor or from exit loan made to the reorganized debtor), the money has to get to creditors.

There are only two ways that can happen in chapter 11: confirmation of a plan or a structured dismissal. During what we denominate as Stage 4:

- Negotiations take place over the terms of a potential plan.

- If there is going to be a plan filed, it gets drafted and filed.

- The plan proponent (usually but not always the debtor—except in subchapter V, in which case it can only be the debtor) files the plan and tries to get it confirmed.

- If a plan cannot be confirmed, parties may seek a structured dismissal.

Stage 5: Exit & Post-Confirmation

A debtor is considered to generally have “exited” its chapter 11 case upon (a) confirmation of a plan of reorganization or liquidation; or (b) entry of an order dismissing the case. In the event a case is dismissed, the dismissal order is the effective end of the case.

In the case of a plan being confirmed, however, the post-confirmation period in a reorganization scenario may include significant events and milestones for creditor distributions, sales of assets, claims reconciliation, and other administrative matters before the plan is deemed “substantially consummated” by the bankruptcy court and the case is closed. In the event a plan of liquidation is confirmed, there is likely to be the creation of a post-confirmation trust for the benefit of creditors.

A post-confirmation trustee (often called a “creditor trustee” or “liquidating trustee”) is commonly appointed to oversee the trust. The trustee’s duties often include collecting the property of the debtor, selling assets, making distributions to creditors, prosecuting litigation claims including chapter 5 causes of action, and reconciling and objecting to creditor claims, among others. A trust may remain open for several years as it administers claims, especially if it pursues or defends contested litigation claims with the debtor’s creditors, former equity holders, directors and officers, and other parties.

The Chapter 11 Timeline: A Chart

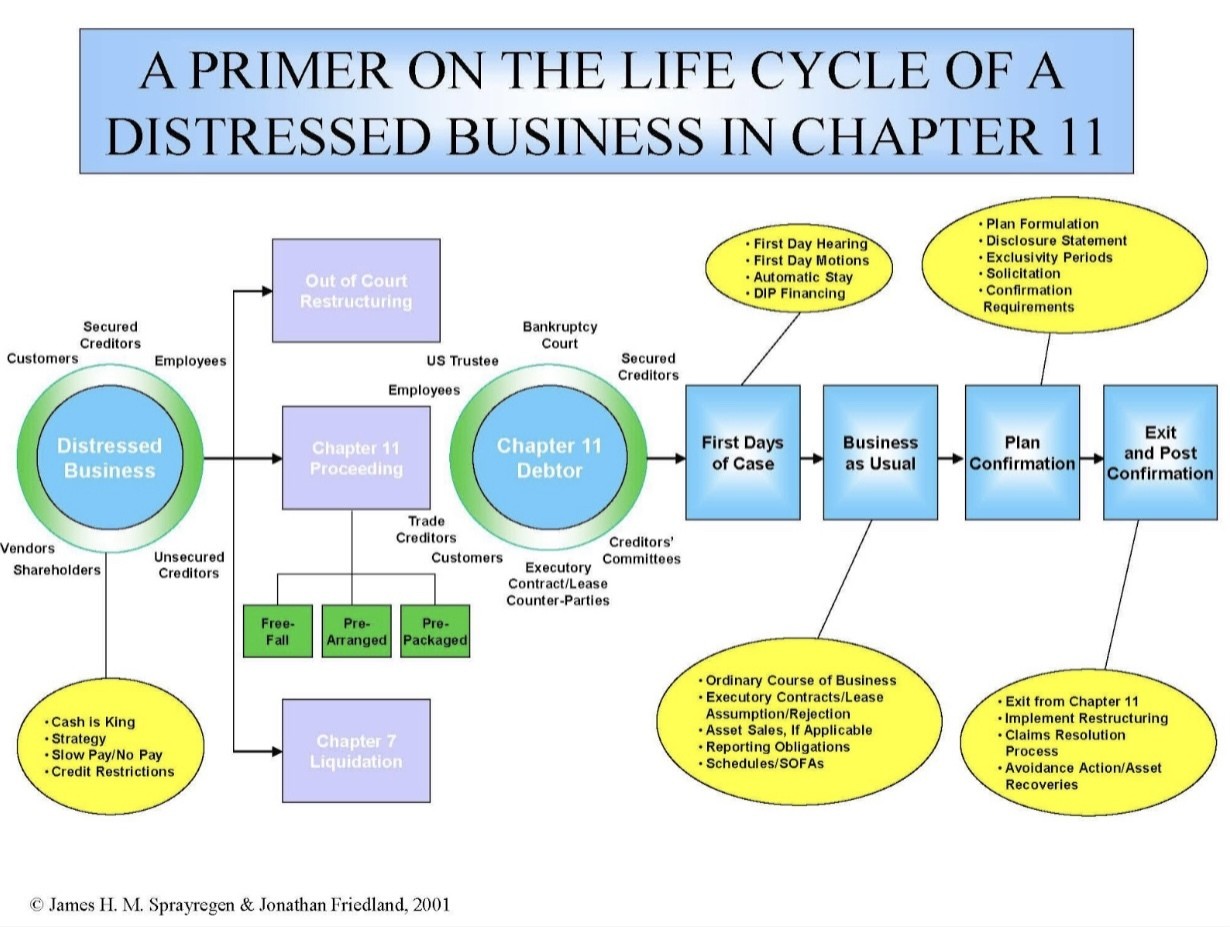

With all of this context, we can now pull the camera even further back to share an image that represents the overall lifecycle of a distressed company undergoing a “true” or “classic” chapter 11 (also sometime referred to as a “free-fall” chapter 11). That is, a chapter 11 case which is neither prepackaged nor prearranged.

And now that we understand the basic mechanics of a “typical” chapter 11 case, we can begin digging into more of the key concepts and features of chapter 11 necessary to build a foundation for understanding business distress more generally.

[Editors’ Note: This article, while written to be read and understood on a standalone basis, is part of a series. To read Installment 1, which includes a table of contents and links to every article in the series, click here.

The authors are corporate restructuring and insolvency attorneys. Read more about three of them at the end of Installment 1.

Understanding all this stuff in the context of bankruptcy is important, but not every distressed company winds up in bankruptcy. So, you also need to understand how it works outside of bankruptcy. Read Installment 6 to read the rest of the story.

To learn more about this and related topics, you may want to attend the following on-demand webinars (which you can listen to at your leisure and each includes a comprehensive customer PowerPoint about the topic):

©2020. DailyDACTM, LLC d/b/a/ Financial PoiseTM. This article is subject to the disclaimers found here.

- In an earlier article Friedland co-authored, he wrote: “Indeed At the outset, however, we thought it useful to explain why we think that the ultimate goal of the restructuring market-whether in an out-of-court setting or in Chapter 11-to maximize creditor recoveries. We see four primary reasons for this primacy: two are economic, one is a matter of corporate governance and the third is a matter of congressional intent:

- First and foremost, the U.S. economy is market-driven. Market participants, naturally enough, seek the highest returns possible for their investments. The restructuring market is no exception. In fact, for reasons touched upon in this article, restructuring market participants (or “vulture investors,” as they are sometimes labeled) can expect to take high risks and reap commensurately high rewards if they are successful;

- Second, a restructuring market that maximizes creditor recoveries is a necessary component of a broader efficient capital market because it maximizes debt capacity for healthy borrowers. In other words, a healthy restructuring market that maximizes creditor recoveries will decrease structural credit risk by mitigating “loss severity”;

- Third, as an entity enters the zone of insolvency, the fiduciary duties owed by the board of directors and management to the corporation, the benefits of which normally flow to shareholders, may extend to creditors. Such a duty may require directors and officers to maximize value for the benefit of the enterprise’s stakeholders by selling the enterprise, whether as a whole or in its constituent pieces; and

- Fourth, when it enacted the Bankruptcy Reform Act of 1978, Congress stated that a major goal of the then-new Chapter 11 was maximizing creditor recoveries.”

James Sprayregen, Jonathan Friedland, Roger Higgins, Chapter 11: Not Perfect, But Better Than The Alternatives, JOURNAL OF BANKRUPTCY LAW AND PRACTICE, Vol. 14, No. 6 (2005) (internal citations omitted).

About Jonathan Friedland

Jonathan Friedland is a principal at Much Shelist. He is ranked AV® Preeminent™ by Martindale.com, has been repeatedly recognized as a “SuperLawyer” by Leading Lawyers Magazine, is rated 10/10 by AVVO, and has received numerous other accolades. He has been profiled, interviewed, and/or quoted in publications such as Buyouts Magazine; Smart Business Magazine; The M&A…

About Jack O'Connor

Jack is a corporate and restructuring partner at Levenfeld Pearlstein. Jack’s practice covers a range of healthy and distressed business engagements. He is widely recognized for his excellent work as a restructuring attorney including recognition by various organizations for his strategic thinking and tactical expertise, including SuperLawyers Magazine, Leading Lawyers Magazine, and the Turnaround Management…

About Hajar Jouglaf

Hajar is an associate with Much Shelist in both its Business Transactions Group and its Restructuring & Insolvency Group.

Related Articles

PUBLIC NOTICE OF CHAPTER 11 SALE: Solar Biotech, Inc.

Kuney’s Corner – Cram Down: When the Creditor Says “No”

The Chief Restructuring Officer: Architect, Leader, & Change Agent

Opening the Kimono: Operational and Financial Reporting Obligations at the Outset of a Chapter 11 Case

90 Second Lesson: When a Seller of Real Property Files for Bankruptcy Before Closing

Subchapter V of Chapter 11: A User’s Guide

Session expired

Please log in again. The login page will open in a new tab. After logging in you can close it and return to this page.