- Home »

- Business Bankruptcy »

- Dealing with Corporate Distress 08: Preventing Forest Fires with First Day Motions in Chapter 11

Dealing with Corporate Distress 08: Preventing Forest Fires with First Day Motions in Chapter 11

The ABCs of ABCs, Business Bankruptcy & Corporate Restructuring/Insolvency

In this installment, we take you on a tour of the time leading up to the filing of a chapter 11 case and the days that immediately follow. Mostly, we’re referring to first day motions.

Before we dive into first day motions, however, you should understand that a debtor and its professionals are typically doing many other things immediately before and after they file a chapter 11 petition. For example:

- Continuing to explore alternatives to chapter 11

- Negotiating with various parties

- Working on the schedules and SOFAs

- Creating and implementing a communication plan

Controlling the Chaos of a Chapter 11 Filing & Seeking Emergency Relief

We explain in Installment 5 why first day motions are necessary, but because we know you’re busy, we summarize it for you here:

Filing a chapter 11 is a disruptive event for all parties involved. It poses risk to the debtor’s ongoing operations, especially in light of the fact that the automatic stay prevents the debtor from taking actions that are routine and necessary outside of chapter 11.

Debtors can prepare for and address many of these issues by presenting first day motions with the bankruptcy court—usually on an emergency basis—to seek immediate relief from the restrictions imposed by the Bankruptcy Code through “first day orders.” The first day relief ensures that a debtor (now debtor-in-possession) can continue operating its business with as little interruption as possible to achieve its goals in chapter 11.

Some first day motions are designed to obtain first day orders that override specific statutory defaults of the Bankruptcy Code. For example, relieving the debtor from prohibitions against making payments to certain creditors on account of prepetition debts. More generally, first day motions are filed to facilitate the debtor’s entry into chapter 11 with as little business disruption as possible.

Preparing First Day Motions

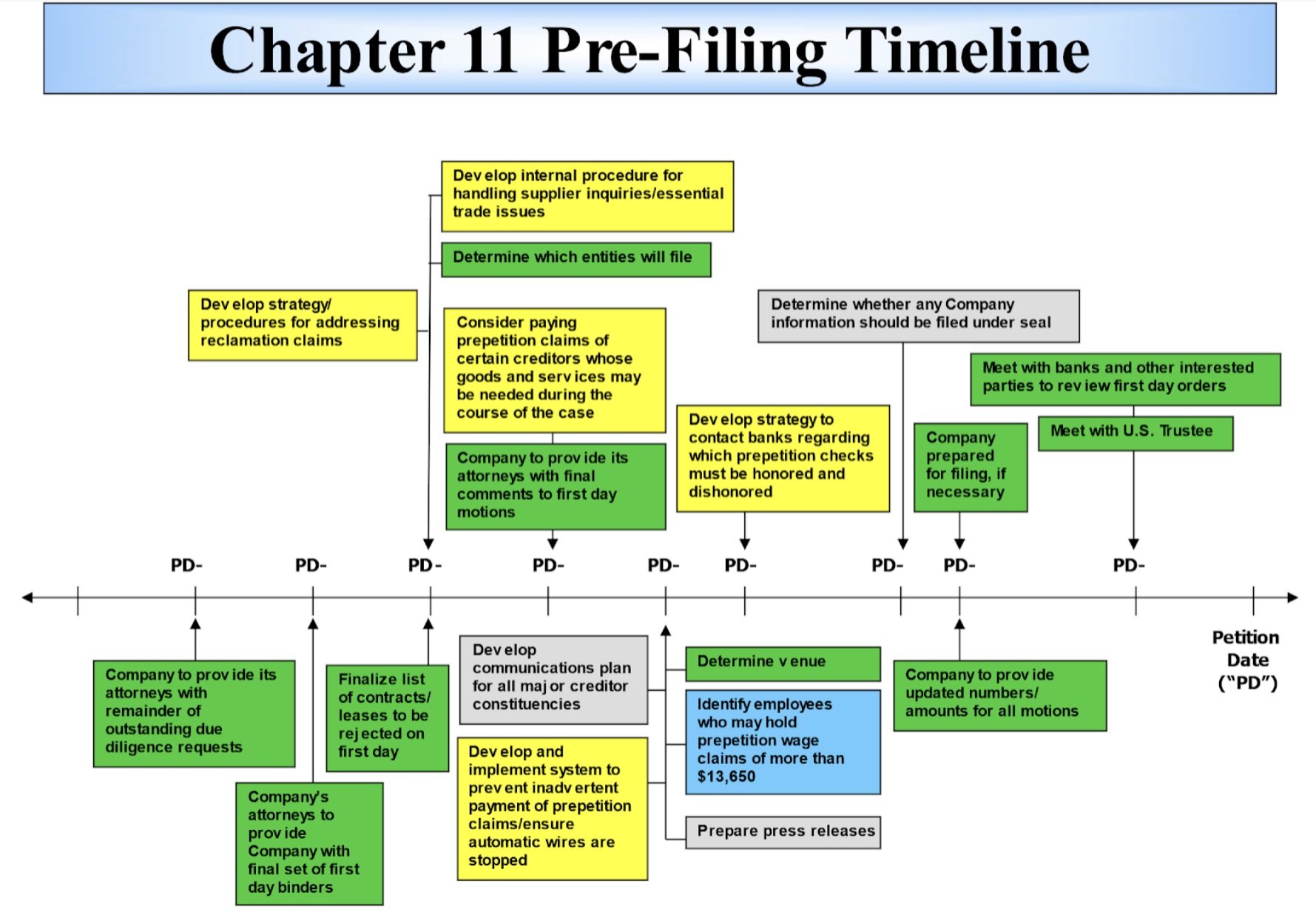

Attorneys, in coordination with the debtor’s senior management, and sometimes with significant help from other corporate restructuring professionals, are the ones who draft the first day motions. Depending on the urgency of filing for chapter 11, the timeline for preparing and filing first day motions may range from as little as several days to as long as several months. In emergency situations, a chapter 11 may be filed without any first day motions. A “typical” pre-filing timeline may look something like this:

The pre-filing timeline above sets forth some of the major tasks and issues that will need to be completed or addressed before the company files for bankruptcy (hence the acronym “PD,“ or “before petition date”), but it’s not meant to be exhaustive. This timeline will be—and must be—highly fluid, which needs to be considered when creating it. Things change very rapidly in a distressed situation, and you need to be flexible; rigidity is a bad thing in our world.

The company’s attorneys will work with it (and any other professionals it has engaged) to identify the most pressing issues that will need to be addressed in its first day motions, then work to file them within as short a timeframe as possible once the petition is filed.

When addressing critical issues in chapter 11, like access to cash and financing on an emergency basis, the bankruptcy court must balance the urgency of a debtor’s need for immediate relief with other parties’ right to due process. The result is that most of the first day orders that are granted by the bankruptcy court will grant no more than interim relief. That is, the bankruptcy court will typically grant a motion to the limited extent necessary to prevent the debtor from suffering irreparable harm. This gives creditors the opportunity to file objections or otherwise negotiate with the debtor regarding the terms of any final order entered later in the case.

The First Day Declaration

In many chapter 11 cases, the debtor will submit a “first day declaration,” or “first day affidavit,” which lays out the factual background surrounding the debtor’s history, financial affairs, and grounds for filing for bankruptcy relief. The first day declaration is a sworn statement made by an individual who is keenly familiar with the debtor, typically the debtor’s CFO, CEO, or CRO—“Chief Restructuring Officer.”

The first day declaration is not a motion, but it is incorporated into each first day motion by reference, therefore making it part and parcel with first day relief in chapter 11. The first day declaration typically includes summaries of each of the debtor’s first day motions and the specific factual underpinnings upon which the debtor seeks relief under each motion. In turn, each first day motion will refer back to the first day declaration as the factual support for the history and relief sought by the debtor.

You can look at the first day declaration as a litigation convention. Here’s what we mean: any court’s job (i.e., not just a bankruptcy court’s) is to weigh evidence to decide what the relevant facts of the matter are. Once it decides (“finds”) what those facts are, a court considers the law to determine if a party seeking some relief is entitled to that relief under the law. Instead of having to listen to testimony, many courts permit a party to proffer (“submit”) a declaration of what its witness would say if called to testify, as long as the witness is available to be cross-examined. This is a very efficient way of proceeding. This is what first day declarations are all about.

First Day Motions

Each chapter 11 case has its own unique set of issues and complexities, thus requiring some debtors to file certain first day motions that others will not. Some first day motions are fairly ubiquitous. They include the following.

Cash Collateral & Postpetition Financing

Without sufficient access to cash, either from ongoing revenues or by obtaining additional financing postpetition, the debtor’s viability as a going concern is severely threatened. Most debtors, therefore, file one or more first day motions specifically aimed at addressing access to cash. These are the “cash collateral” motion and the “DIP financing” motion, commonly referred to collectively as the “postpetition financing” motions.

Cash Collateral

Cash collateral motions are necessary to allow a debtor to use cash in which a lender has a security interest, because, in bankruptcy, a debtor is prohibited from using a secured creditor’s cash collateral without court authority or the consent of that secured creditor who has an interest in cash. When the secured creditor consents to the use of its cash collateral, it will commonly enter into an agreed order with the debtor, governing the debtor’s use of that cash collateral and granting the secured creditor additional protections in connection with the debtor’s use.

If the secured creditor does not consent to the debtor using its cash collateral, the debtor may nonetheless use it if it can provide the secured creditor with adequate protection. Adequate protection is usually given in the form of cash payments, additional or replacement liens, or other relief deemed to be the “indubitable equivalent” of the lender’s interest in the collateral. We discuss these concepts in much greater depth in Installment 14.

DIP Financing

Chapter 11 debtors are generally so strapped for cash (if they weren’t, they likely wouldn’t be in bankruptcy) that the ability to use their own cash is simply not sufficient. So many—if not most—debtors need to borrow money during their chapter 11.

A problem exists because most chapter 11 debtors enter bankruptcy with liens on all their assets, and most lenders typically require collateral.

Bankruptcy Code § 364 addresses this problem by balancing the debtor’s need for new credit with a secured creditor’s right to have the benefit of the liens it bargained for prepetition.

Taking a step back, when a debtor incurs unsecured debt in the ordinary course of business, that debt is generally an administrative expense under Bankruptcy Code § 503(b)(1). This debt (i.e., claim) will be paid ahead of prepetition unsecured claims. Trade vendors will typically sell to chapter 11 debtors on credit because of this protection.

Trade credit, even assuming a debtor can get it during a chapter 11 case, is often insufficient, thus requiring additional borrowing during the case. Moreover, the willingness of trade vendors to extend credit is often dependent, at least in part, on the debtor having traditional DIP financing in place.

One attribute of what we call traditional DIP financing is that the lender is typically granted a “superpriority” administrative claim senior to regular administrative claims against the debtor and a lien that is either superior to, or at least pari passu with, the liens of prepetition senior secured creditors.

We suggest you take the time to read Dealing With Distress for Fun & Profit – Installment #17 – Overview of DIP Financing and Cash Collateral Motions to dive just a little deeper on this topic.

Cash Management Systems

Operational guidelines from the U.S. Trustee generally require, among other things, that a chapter 11 debtor close its prepetition books and records, and bank accounts, and in turn, open new DIP accounts and use new business forms that clearly designate that the debtor is a “debtor in possession.” These rules are imposed under the Bankruptcy Code, because Congress sought to make clear, in the case of a debtor whose name may be the same or similar to other businesses (e.g., a local Domino’s Pizza franchise) that a specific business is informing the world that it is in chapter 11 after the petition date. This avoids confusion for the outside world. But in the case of larger companies, it is hard to argue that their creditors would be unaware of their status as a chapter 11 debtor. Plus, the cost involved in changing over business forms, accounting systems, and other cash management matters would come at a significant cost to a debtor that is already likely to be strapped for cash.

To avoid these issues, the debtor will seek a variance from these guidelines by filling another key first day motion requesting authority under §§ 363 and 105 to allow it to do certain things like:

- Maintain preexisting bank accounts

- Continue using its prepetition business forms

- Continue using existing cash management systems

- Continue using preexisting investment guidelines

- Grant “superpriority” status to postpetition intercompany claims.

Depending on the debtor’s needs, these motions may be lengthy and complex, or simple and straightforward. Without this relief, a large chapter 11 debtor’s operations may come to a standstill while the debtor changes its financial system. The continued use of existing systems is a more efficient alternative, and it is routinely approved.

Wages & Employee Benefits

An additional means of ensuring that the debtor transitions smoothly into bankruptcy is by filing a first day motion seeking authority to pay prepetition wages and employee benefits.

- 507(a)(4) of the Bankruptcy Code gives statutory priority to claims for wages (and certain benefits) earned within 90 days of the bankruptcy filing (capped at $13,650 as of 2021). It’s usually uncontroversial for a bankruptcy judge to authorize the debtor to pay its employees up to the amount of their wages and benefits that may be accrued but unpaid as of the petition date, up to the amount of the statutory claim cap. By filing a motion to pay these claims, the debtor can retain employees who might otherwise be tempted to leave, and avoid business disruptions that might frustrate reorganization efforts.

Utilities

Regardless of the type of business a debtor operates, utility services (electric, gas, water, etc.) are necessary for the debtor to continue to run its business after filing for chapter 11 relief.

Sections 366(a) and (b) of the Bankruptcy Code prohibit utility providers from suspending or altering service during the first 20 days of a bankruptcy case. These sections also provide that after this 20-day period expires, a utility provider can terminate service if it has requested, but not been provided, “adequate assurance of payment.” As a result, one of the standard first day motions filed by a debtor will seek a first day order that deems the debtor’s various utility providers to be “adequately assured” of future performance by the debtor, as well as establishing procedures for a utility provider to determine whether it is adequately assured of future payment.

These procedures may take many different forms, depending on the circumstances of a case, but often they will incorporate a mechanism by which a utility provider can demand, and the debtor will make, a security deposit with the utility provider to protect the utility provider against nonpayment by the debtor while the bankruptcy case is pending.

Taxes

Another common first day motion will seek authority for the debtor to pay certain prepetition state and local taxes, such as sales, use, franchise, or other similar taxes and fees, in the ordinary course of business.

Because taxing authorities are granted special priority over other creditors under the Bankruptcy Code, a first day motion seeking to pay prepetition tax amounts will typically be uncontroversial, since these priority claims stand to be paid in full ahead of many other claims against a debtor’s estate. See Bankruptcy Code § 507(a)(8).

Insurance

Most (if not all) businesses carry insurance coverage protecting themselves and their creditors against losses taking place during the course of their operations. And frequently, these businesses pay their insurance premiums under the terms of a premium financing agreement (“PFA”).

At the time of a bankruptcy filing, a debtor may have outstanding prepetition insurance premiums that it owes. If these amounts are not paid, insurance providers will not continue providing coverage to the debtor on a postpetition basis. Additionally, in the case of a debtor who has entered into a prepetition PFA, additional premium payments will come due under the PFA postpetition. A first day motion pertaining to insurance policies therefore proves useful, and often necessary. Under this first day motion, a debtor will seek authority to pay outstanding prepetition premiums, as well as authority to continue paying postpetition amounts in the ordinary course of business to remain insured and to protect itself, its bankruptcy estate, and creditors from losses that may occur after filing chapter 11.

First Day Motions Addressing Chapter 11 Administrative Issues

There are a number of first day motions that may be filed in a case for purposes of administrative efficiency for the bankruptcy court, clerk’s office, and parties involved in the cases. Administrative motions may include:

- A motion requesting that the bankruptcy court hold an emergency hearing on the first day motions so that no time is wasted on first day motions that seek true emergency relief;

- A motion seeking “joint administration” to procedurally consolidate bankruptcy case dockets of affiliated debtors under one main docket;

- A motion to use a consolidated list of creditors where there are multiple affiliated debtors with overlapping creditors;

- A motion to appoint a third party to act as the court’s agent for purposes of claims administration, and to serve important documents filed in the case on creditors and other parties entitled to notice of court filings in the case;

- A motion to establish streamlined procedures for the payment of retained professionals within the case;

- A motion seeking to extend the time in which the debtor must file its bankruptcy schedules and SOFAs, among others; and

- A motion requesting the bankruptcy court to set a deadline for the filing of proofs of claim, often referred to as “Bar Date.”

Other First Day Motions

Each chapter 11 case is different and may require additional, specialized relief depending on the debtor’s business and industry, and potentially the location of the bankruptcy court where the case is filed. As such, additional first day motions may be necessary. For example, debtors operating sales or retail businesses may wish to continue honoring prepetition customer programs to avoid losing patronage from customers while the case is pending. Some retail debtors may seek to conduct going-out-of-business (“GOB”) sales if the burdens of administrative expense claims outweigh the benefits of continuing operations, or the value to be realized for its inventory is greater through a GOB sale.

Debtors with large management teams who are truly essential to the debtor’s continued operations motions may file first day motions seeking to establish “key employee retention programs,” or “key employee incentive programs” (“KERP” and “KEIP” motions). Depending on where the case is pending, a debtor may file a first day motion that seeks to allow and pay prepetition claims of so-called “critical vendors”—trade creditors whom the debtor deems so integral to its own ongoing business and reorganization efforts that it seeks to pay them for their outstanding prepetition claims to ensure business continuity on a postpetition basis.

Additionally, certain motions that may be filed at varying times during a chapter 11 case may be deemed necessary to file as first day motions. These can include motions to reject, assume, or assume and assign certain executory contracts or unexpired leases; or applications to employ professionals in the case to assist the debtor in administering its affairs in chapter 11.

Understanding, drafting, and filing the appropriate first day motions is just one part of this process. There are a number of additional steps that must be taken before first day motions will be granted and a bankruptcy judge will enter first day orders. For example, the first day motions must be set for hearing and argument (if necessary) to show the bankruptcy judge that the relief sought by each first day motion is appropriate under the circumstances of the case.1

But that’s only a small part of what needs to happen. Getting any particular first day order, like getting any order from any court, is never the end unto itself. Rather, an order is a means to an end. So, taking a critical vendor motion as an example, let’s assume you file it and get the relief you seek. What then? Well, there needs to be a plan to get critical vendors paid. We’re not going to dive deeply into what one looks like here, but let it suffice to say that there is work that the business people need to do both before the motion is filed and after it is granted. That work has to be allocated to the right people, and they need to be educated on what to do (and not do).

A Final Note on Effectively Transitioning to Chapter 11

While first day motions can facilitate a debtor’s transition into chapter 11, they are not a cure-all. To the extent possible, the debtor should work to reach agreement with the key parties affected by its various first day motions before presenting them in court. Doing so will avoid time and expense for the debtor, the bankruptcy court, and creditors generally. And doing so will serve the greater overall purpose of the first day motions: facilitating the debtor’s smooth entry into chapter 11.

In our next installment, we shift our focus away from debtors and turn our attention to the perspective of a creditor to better understand the nature of claims, both in and out of bankruptcy.

[Authors’ Note: First Day Motions: A Guide to the Critical First Days of a Bankruptcy Case, published by the American Bankruptcy Institute, is the single best resource out there to learn more about first day motions.

Editors’ Note: This article, while written to be read and understood on a standalone basis, is part of a series. To read Installment 1, which includes a table of contents and links to every article in the series, click here.

The authors are corporate restructuring and insolvency attorneys. Read more about three of them at the end of Installment 1.

Understanding all this stuff in the context of bankruptcy is important, but not every distressed company winds up in bankruptcy. So, you also need to understand how it works outside of bankruptcy. Read Installment 9 to read the rest of the story.

To learn more about this and related topics, you may want to attend the following on-demand webinars (which you can listen to at your leisure and each includes a comprehensive customer PowerPoint about the topic):

©2021. DailyDACTM, LLC d/b/a/ Financial PoiseTM. This article is subject to the disclaimers found here.

- As a practical matter, your authors follow the common practice in complex chapter 11 cases of preparing, filing, and serving—on as many creditors as possible—an agenda of the first day motions that will be heard by the court on a given hearing date. This serves to not only organize the first day motions for the court and key parties in a case but helps to ensure that parties in interest are given notice of the first day motions and hearing, increasing the likelihood that any emergency relief sought will be granted.

About Jonathan Friedland

Jonathan Friedland is a principal at Much Shelist. He is ranked AV® Preeminent™ by Martindale.com, has been repeatedly recognized as a “SuperLawyer” by Leading Lawyers Magazine, is rated 10/10 by AVVO, and has received numerous other accolades. He has been profiled, interviewed, and/or quoted in publications such as Buyouts Magazine; Smart Business Magazine; The M&A…

About Jack O'Connor

Jack is a corporate and restructuring partner at Levenfeld Pearlstein. Jack’s practice covers a range of healthy and distressed business engagements. He is widely recognized for his excellent work as a restructuring attorney including recognition by various organizations for his strategic thinking and tactical expertise, including SuperLawyers Magazine, Leading Lawyers Magazine, and the Turnaround Management…

About Hajar Jouglaf

Hajar is an associate with Much Shelist in both its Business Transactions Group and its Restructuring & Insolvency Group.

Related Articles

PUBLIC NOTICE OF CHAPTER 11 SALE: Metavine, Inc.

What Secured Lenders Should Know If Their Borrower Files for Bankruptcy

90 Second Lesson: What is a “Professional Fee Carve-Out” in Chapter 11?

Dealing with Corporate Distress 15: Digging into DIP Financing & Cash Collateral Motions in Bankruptcy

Third-Party Litigation Funding (TPLF) and Ethical Issues In Bankruptcy

Assignee Unknown: The Curious Cases of SmartLabs, Shine Bathroom Technologies, Liftopia, GlassPoint, SolarReserve, Maker Media, & Toymail

Session expired

Please log in again. The login page will open in a new tab. After logging in you can close it and return to this page.